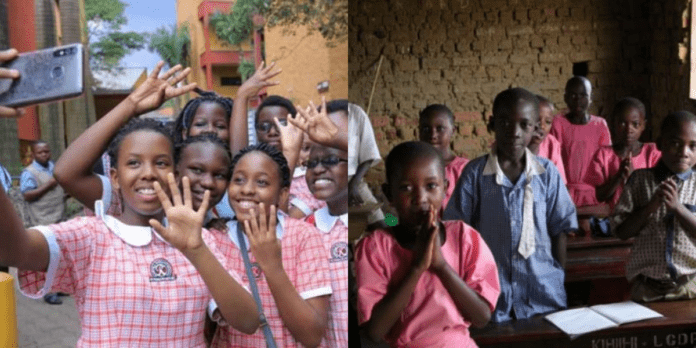

The skyrocketing fees in Ugandan schools have left many parents struggling to keep their children in class. With the average income in Uganda barely exceeding 3 million UGX per month, the burden of affording quality education is pushing families into debt. This raises the pressing question: has education in Uganda become a privilege for the wealthy, leaving the poor to grapple with limited opportunities?

In Kampala, Wakiso, and Mukono, parents must part with at least 1.8 million UGX per term for tuition at prestigious schools, excluding other costs like uniforms and school requirements. For a family with two children, this translates to over 10 million UGX per term, a figure that is simply unattainable for the average Ugandan. Even nursery schools in these areas charge a minimum of 1 million UGX, prompting many to question: is this about education or exploitation?

Ironically, university education in Uganda is often cheaper than nursery, primary, or secondary school. This discrepancy stems from the fact that university tuition is regulated, unlike the lower education levels where fees are unchecked. The result? Many children drop out or are forced into superb schools that fail to prepare them for the next academic stage. Others repeat grades, leading many families to give up on education entirely.

Paul Mugalu, an economist and father of two, describes the system as “man-eat-man,” emphasizing the urgent need for education to be treated as a public good. “The same people making laws own these schools. Unless the Ministry of Education prioritizes equitable access, this crisis will persist,” he says. The reality is grim: even for families who manage to afford the exorbitant fees, the return on investment is questionable. Graduates often start with meagre salaries of 500,000 UGX in corporate jobs, leaving parents who spent millions questioning if it was worth it.

President Museveni, on November 20, 2024, condemned the charging of fees in government schools, calling it a major cause of school dropouts. He reiterated that Universal Primary Education (UPE) and Universal Secondary Education (USE) were designed to be free and urged parents to challenge headteachers imposing extra costs. Despite this directive, many government schools continue to charge fees, and where parents refuse to pay, the quality of education provided is alarmingly poor. This creates a vicious cycle, leaving students ill-prepared to compete academically.

In February 2023, the Parliamentary Committee on Education investigated exorbitant fees charged by government-aided secondary schools. MPs Sarah Opendi and Samuel Opio Acuti highlighted how top schools under the USE program were demanding over 2 million UGX per term, effectively locking out children from low-income families. The committee recommended capping fees between 260,000 and 1.6 million UGX depending on the school’s location and resources. However, to date, these recommendations remain unimplemented. The same schools now charge upwards of 2.5 million UGX per term, with admission fees adding another layer of financial strain. For instance, Seeta High School demands an admission fee of over 600,000 UGX, tuition of 2.5 million UGX, and additional costs that bring the total to nearly 4 million UGX per term. How many families can realistically afford this?

The rise of “education tourism” in urban areas has exacerbated the problem, with parents flocking to flashy schools in search of better performance. Humphrey Anjoga, a former lecturer and director of a management institute, explains that these schools capitalize on the growing urban economy and changing living standards. “The government must transform traditional schools and standardize private ones to reduce the demand for high-end institutions,” he suggests. Additionally, he advocates for removing VAT on school commodities to alleviate costs.

Private school administrators, however, defend their fees. Lazarus Olupot, headteacher at Seeta Junior Primary School, claims their fees reflect the quality of services offered. “We ensure our boarding pupils are comfortable, well-fed, and taught by the best teachers. This is evident in our excellent performance,” he says. While these claims may hold some truth, they do little to address the systemic exclusion of low-income families.

The gap between policy and practice remains stark. Despite warnings that school administrators flouting regulations could face up to a year in prison, enforcement is lacking. The government’s failure to regulate fees has allowed education to become a tool of socioeconomic stratification. Meanwhile, initiatives like UPE and USE have been undermined by poor funding and corruption, leaving them as mere shadows of their intended purpose.

The question of education as a public good demands urgent action. Uganda’s legislators must prioritize the regulation of school fees and invest in improving the quality of government schools. Transforming institutions like Bukedi College, Mwiri College, and Kigezi College could reduce dependence on high-end private schools. Removing VAT from school supplies and standardizing fees across private and public schools are critical steps to ensure equity.

Education is the cornerstone of a nation’s development, yet in Uganda, it is becoming a privilege rather than a right. If unchecked, the current system will continue to widen the gap between the rich and poor, leaving millions of children without a future. It is time for the government and stakeholders to act decisively to restore education’s role as a tool for opportunity and social mobility.